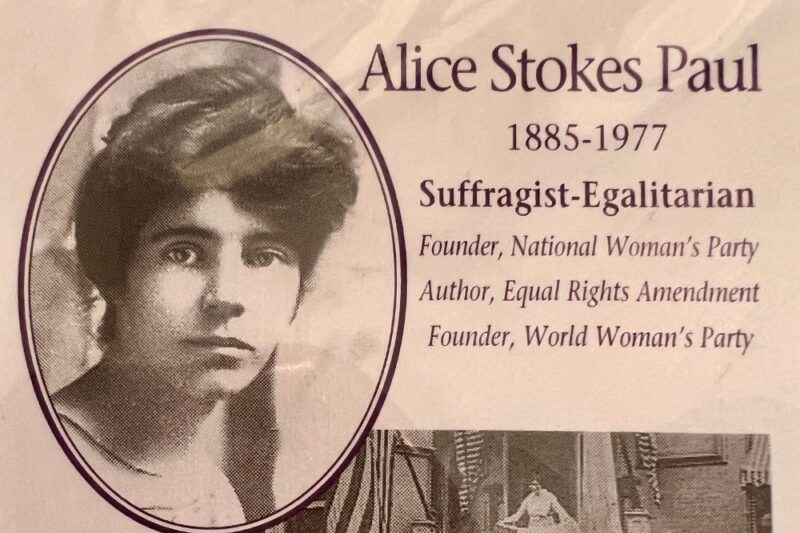

Alice Paul might not be a household name today, but her life’s work greatly shaped the world we live in. She endured repeated imprisonments and the agony of forced feeding, made herself a pariah to some, and appealed directly to her President to bring the right to vote to US women. This New Jersey native was a pioneer in discussions of gender equity. Read on to learn more about Alice Paul’s work to open suffrage to all the world’s women and to pass the Equal Rights Amendment to the US Constitution.

Raising a Rabble Rouser

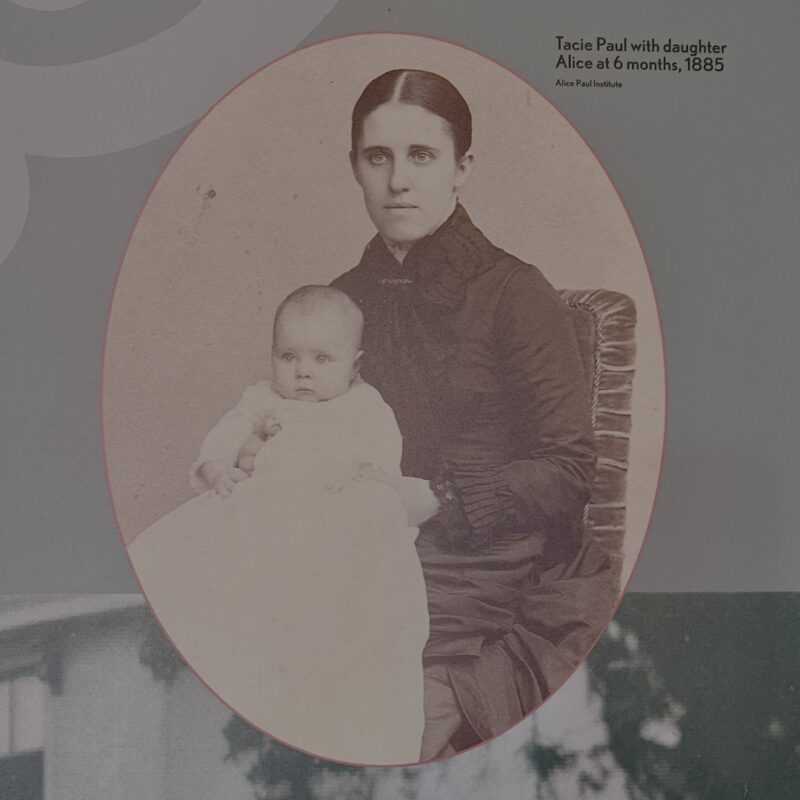

Alice Paul was born in 1885 on a farm her family dubbed Paulsdale, near what is now Mount Laurel, New Jersey. She and her younger siblings were raised as Hicksite Quakers, a liberal branch of Quakers who were amongst the earliest advocates for the abolition of slavery and generally committed to a belief in equality for all people. Alice’s mother, Tacie Parry, attended college at Swarthmore until she married William Paul and the university denied her a degree based on her marital status. Alice was educated first at Morristown Friends School where her parents’ liberal beliefs were affirmed. She was said to be reserved and shy, yet she rode her horse to the school stables each day and played basketball, field hockey, and tennis.

Alice’s independence in childhood, though natural within her upbringing, was not typical of the era. Consequently, her expectations of what she might do in the world did not reflect the era’s doctrine of “separate spheres” which maintained that women were born to a world of privacy, focusing all their attention on their family’s health and morality. Such a worldview left men the sole occupants of the public sphere through which society was governed. This denial of women’s participation in public life and repression of their academic and professional accomplishments clashed drastically with the gender equity Alice had been raised to believe in. She was pretty sure she could do just about anything she put her mind to.

Read More: 33 Famous Women From New Jersey in Honor of Women’s History Month

Alice earned a Bachelor of Science degree in biology from her parents’ alma mater, Swarthmore. She then went on to earn a Master of Arts degree in sociology and a PhD in economics from the University of Pennsylvania. When she was in her mid-30s, she returned to school and acquired multiple law degrees from Washington College of Law at American University. Alice was no slouch.

“Deeds Not Words”

A vital part of Alice’s education did not come from a classroom. As a young woman, Alice took a steamer ship to England. Ostensibly, her journey was to study at Birmingham University. After attending lectures by Christabel Pankhurst she was pulled to the picket line to demonstrate alongside the Women’s Social and Political Union where she was arrested and imprisoned for the first time.

Despite the damaging physical and psychological effects of forced feeding operations on Alice and the other suffragists who engaged in hunger strikes while held in British prisons, she took the confrontational tactics she’d learned from her sisters abroad back with her to the United States. Christabel’s motto of “deeds not words” had convinced Alice that militant strategy was necessary to end the exclusion of women from public ambitions. She was received as a celebrity upon her return to the States and used that momentum to organize a pivotal event in the fight for women’s equality— a spectacular parade.

Racial Inequity in Her Work for Gender Equity

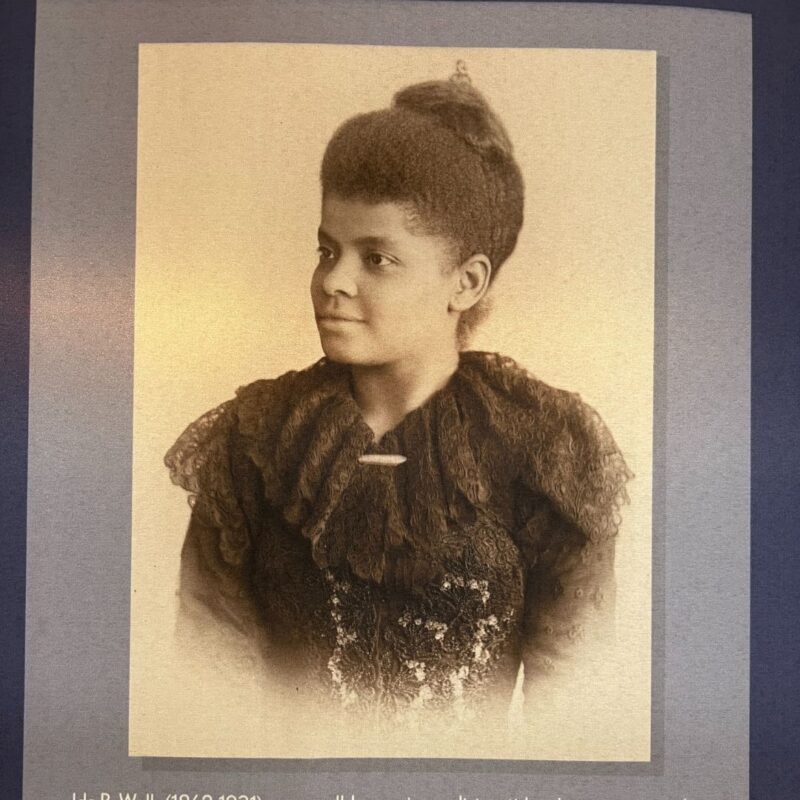

Black women leaders did not capitulate to Alice’s request that they absent themselves from the momentous event that would become known as “The Great Demand.” They showed up as they had originally planned. The parade was organized around the idea that each section of marching women was an argument regarding the accomplishments of the nation’s women. There were state delegations and groups defined by their professions or their university degrees. It was absolutely out of the question that a march purporting to demonstrate women’s dignity and competence would not include the Black women who had fought so hard for each of their accomplishments. At least 25 Howard University graduates; various state delegates and professional representatives; along with Mary Church Terrell, a powerful leader of the National Association of Colored Women; and the legendary Ida B Wells all marched. Ojibwe lawyer Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin marched with the lawyers contingent of the procession to further the long fight for Native American suffrage.

The parade took place on the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration and followed the same route on Pennsylvania Avenue that the inaugural parade would take the next day. Bands played patriotic music. Lawyer and activist Inez Milholland was regal in a costume of Greek robes, riding a white horse as she led the procession. The surrounding crowd of men turned nasty early into the event. Police chose not to intervene as jeering men grew increasingly violent. By the time the Calvary intervened, upwards of 100 suffragists were taken to emergency hospitals. The end result, however, was weeks of favorable publicity from news reporters sympathetic to the women of the movement.

Stalwart + Tireless, Alice did not Back Down

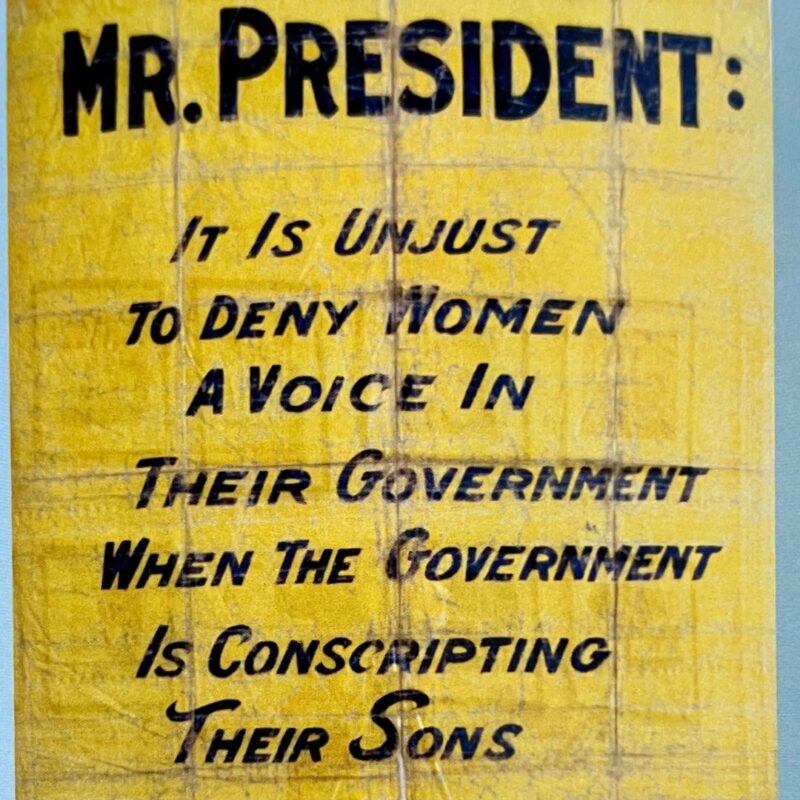

President Woodrow Wilson was far from free of Alice Paul’s organizing efforts following his inaugural parade. His time in office was marked by Alice Paul’s protest actions. Alice and her co-conspirator, Lucy Burns, organized the Silent Sentinels in 1917. President Wilson was unmoored by the women of all ages standing quietly outside the White House gates every day, holding banners demanding the vote. He was not sure what to do with this unprecedented commotion that greeted him each and every time he was driven through the White House entry.

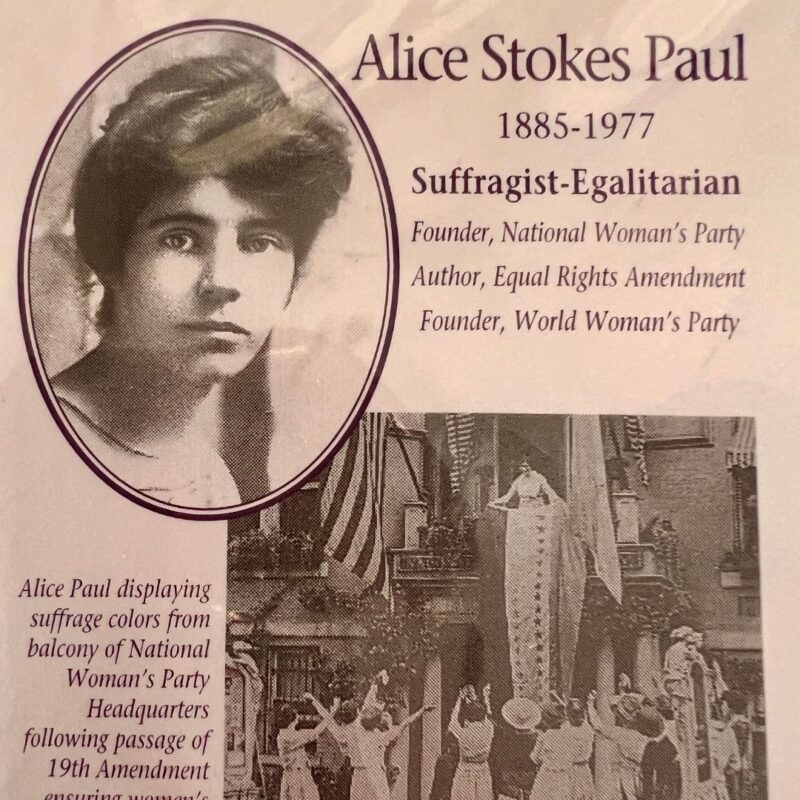

The battle for the vote was consistently met with hostility. The suffragists were called anarchists for upsetting the social order. Alice was again imprisoned and then force-fed when engaged in hunger strikes. Then, on August 18th, 1920, the 19th Amendment — after skidding through the House and Senate by two votes— was signed into law. White women now had the freedom to vote their conscience in all elections, local and national.

Women of color, on the other hand, found themselves subject to poll taxes, literacy tests, fraud, and intimidation that disenfranchised their male contemporaries. Asian-American women who had gained their citizenship as immigrants were excluded from voting until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. In 1929, Puerto Rican women were given the vote only if they were proven to be literate in English. Voting rights were expanded to all Puerto Rican women only in 1935 after decades of activism by local suffragists. It took the 1975 extension of the Voting Rights Act to expand voting access fully. At the time of its passing, Alice Paul was still alive and still in the fight. Alice Paul passed away in July 1977 in Moorestown, New Jersey.

Mother of a Movement

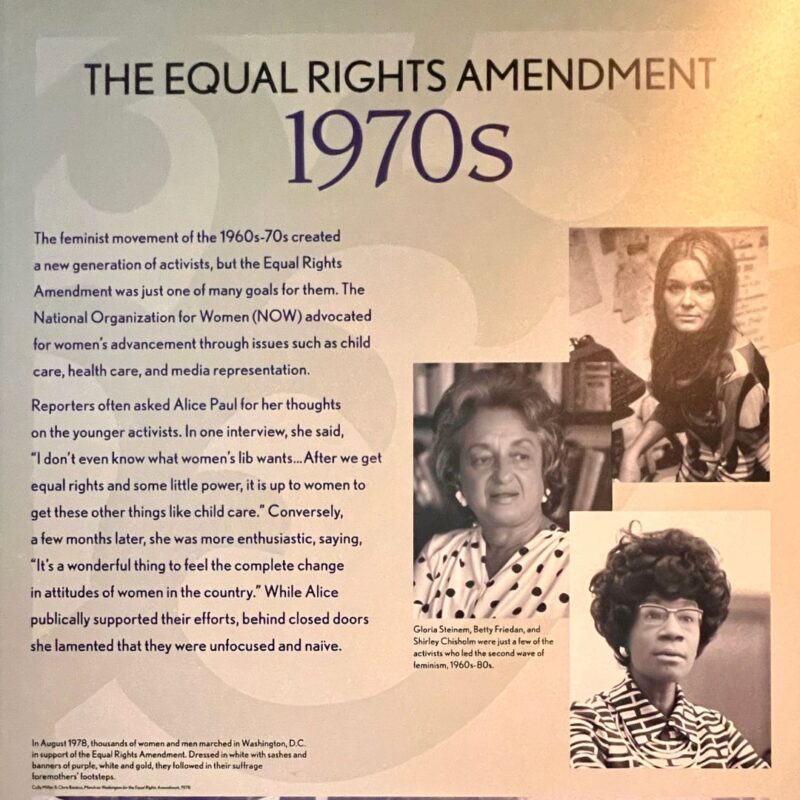

Alice didn’t have or raise children, but future generations of women working toward gender equality have identified her as a foundational parent to their efforts. While fully recognizing her obstinate blind spots on the intersectionality of discrimination and the importance of Black women leaders’ visibility, her work was touted as groundbreaking by Shirley Chisholm, Gloria Steinem, and other second-wave feminists.

The impact of Alice’s activism outlived her. The Equal Rights Amendment that she wrote in 1923 was reintroduced in every session of Congress from then until Virginia finally became the last state to sign on in 2020. Her legacy is global in its reach, too. In 1938, Alice founded the World Women’s Party (WWP) which lobbied the League of Nations to include an equal rights clause in its charter. Article 1 of the United Nations Charter states its goal “To achieve international co-operation … in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.” Today, the UN Commission on the Status of Women is a global policy-making body dedicated exclusively to gender equality.

See More: 46 Women Community Leaders Making a Difference in Hoboken + Jersey City

The Alice Paul Center for Gender Justice

The Alice Paul Center for Gender Justice in Mount Laurel, New Jersey, is a thriving organization situated in the beautiful childhood home of Alice Paul, Paulsdale. The Center welcomes individual and group tours. It is a bustling home for youth, community, and advocacy programs — such as the Girls Leadership Council and the Champions of Equality presentation series. The house hosts happenings big and small, including Family Saturdays Events, author talks, and a wide array of virtual presentations that can be found on the website.